A major breakthrough came in the early 2000s when Japanese researchers stumbled upon a simple formula to turn any type of tissue into powerful stem cells, similar to those in an embryo. The fantasies ran wild. Scientists realized they could potentially make unlimited supplies of almost any type of cell — say, nerve or heart muscle.

In practice, however, the formula for making certain types of cells can prove elusive, and then there’s the problem of getting lab-grown cells back into the body. To date, there have been few demonstrations of reprogramming as a method of treating patients. Researchers in Japan tried a transplant retinal cells in blind. Then, last November, a US company, Vertex Pharmaceuticals, said so may have cured a man’s type 1 diabetes after an infusion of insulin-responsive programmed beta cells.

The concept that startups are pursuing is to collect ordinary cells, such as skin cells, from patients and then convert them into hair-forming cells. In addition to dNovo, a company called Stemson (its name is a portmanteau of “stem cells” and “Samson”) has raised $22.5 million from donors including pharmaceutical company AbbVie. Co-founder and CEO Geoff Hamilton says his company is transplanting reprogrammed cells onto the skin of mice and pigs to test the technology.

Both Hamilton and Lujan believe there is a sizeable market. About half of men suffer from male pattern baldness, some starting in their 20s. When women lose hair, it’s often a more generalized thinning, but it’s no less of a blow to self-image.

These companies bring high-tech biology to an industry known for illusions. There are many false claims about both hair loss remedies and the potential of stem cells. “You have to be wary of scam offers,” says Paul Knoepfler, a stem cell biologist at UC Davis. wrote in November.

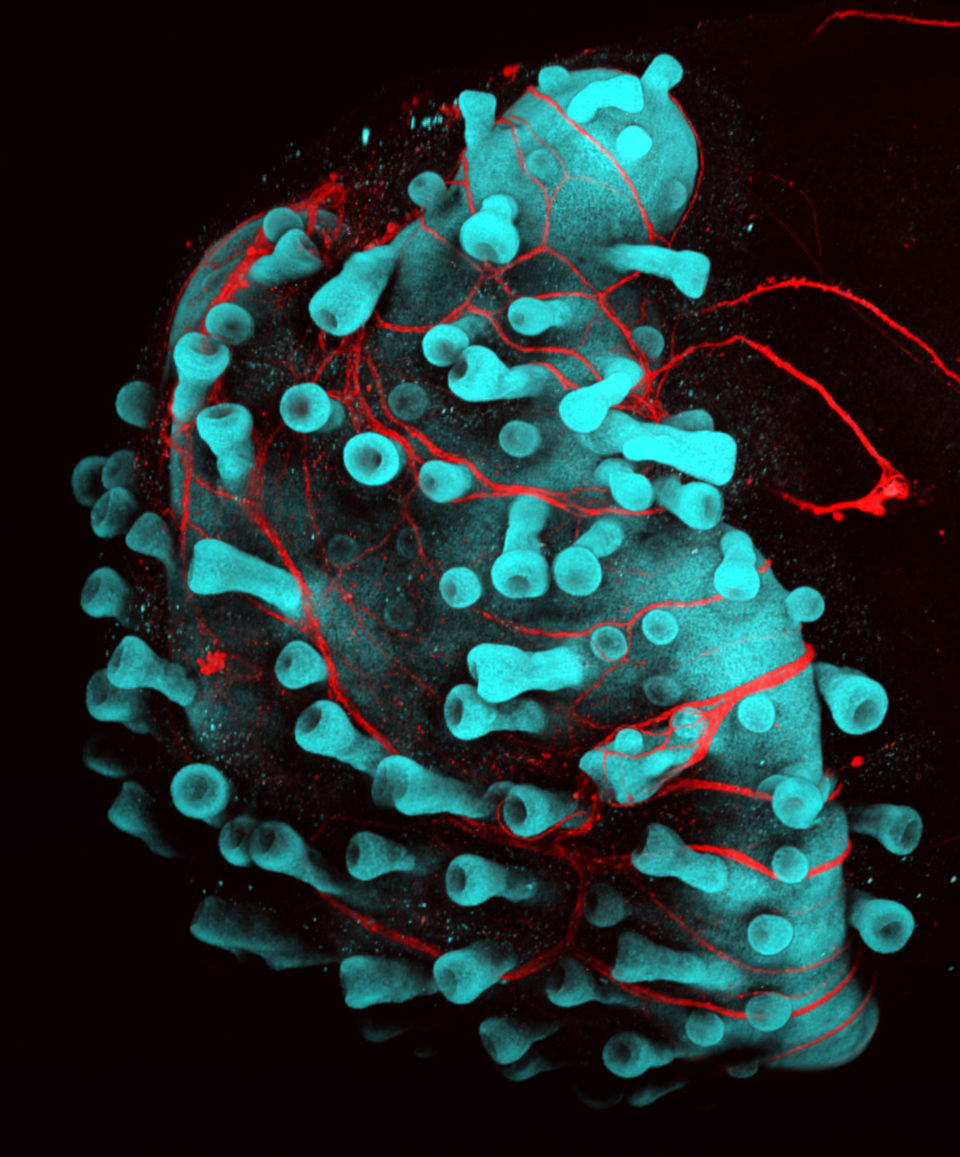

A closeup of a skin organoid covered with hair follicles.

JIYOON LEE AND KARL KOEHLER, HARVARD MEDICAL SCHOOL

Tricky business

So will stem cell technology cure baldness or become the next false hope? Hamilton, who was invited to keynote at this year’s Global Hair Loss SummitHe tried to emphasize that the company still has a lot of research to do, he says. “We saw so many [people] come and say they have a solution. That’s happened a lot with hair, so I have to address that,” he says. “We’re trying to convey to the world that we’re real scientists and that it’s so risky that I can’t guarantee it will work.”

There are currently some approved hair loss medications, such as Propecia and Rogaine, but they are of limited use. Another procedure is to cut strips of skin from a spot where a person still has hair and surgically transplant those follicles to a bald spot. According to Lujan, in the future, lab-grown hair-forming cells could be added to a person’s head with a similar operation.

“I think people will go to quite a length to get their hair back. But initially it will be a customized process and very expensive,” says Karl Koehler, a professor at Harvard University.

Hair follicles are surprisingly intricate organs created by the molecular interaction between multiple cell types. And Koehler says images of mice growing human hair aren’t new. “Every time you see these images,” Koehler says, “there’s always a trick and a downside to translating them to humans.”

Koehler’s lab makes hair shafts in a very different way—by growing organoids. Organoids are small clumps of cells that self-organize in a Petri dish. Koehler says he originally studied cures for deafness and wanted to grow the hair-like cells of the inner ear. But its organoids became skin instead, complete with hair follicles.

Koehler welcomed the accident and now makes spherical skin organoids that take about 150 days to grow until they are about two millimeters in diameter. The tubular hair follicles are clearly visible; He says they’re the equivalent of the downy hairs that cover a fetus.

One surprise is that the organoids grow backwards, with the hairs pointing inward. “You can see beautiful architecture, although there’s a big question as to why they grow from the inside out,” says Koehler.

The Harvard lab uses a supply of reprogrammed cells obtained from a 30-year-old Japanese man. But it’s examining cells from other donors to see if organoids could give rise to hair with distinctive colors and textures. “The demand is absolutely there,” says Koehler. “Cosmetics companies are interested. Their eyes light up when they see the organoids.”