According to Collective Action in Tech, a project tracking the industry’s organizing efforts, every year since the walkout has seen more workers speaking out. The big tech companies’ image as friendly giants had been shattered. Part of the walkout’s legacy, Stapleton says, was “helping people see the gap between how companies present themselves and how they run a business, and what the capitalist machine is and does.”

In 2021, the sheer number of collective actions declined. But that’s because of the nature of those actions shifted, say JS Tan and Nataliya Nedzhvetskaya, who help run the Collective Action in Tech archive.

“Compared to 2018, I think there’s a lot more realism about what organizing workers means and what comes with that,” says Nedzhvetskaya, a PhD candidate at the University of California, Berkeley. “One theory for why we’re seeing this base building is because people realize this is a hard thing to do individually.”

Last year, rather than penning open letters (which can be a fairly quick process), workers began pushing for unionization, a notoriously prolonged ordeal. But creating unions—even if they’re “solidarity unions,” which have fewer legal protections—is an investment in the future. Twelve tech-worker unions were formed in 2021, according to Collective Action in Tech’s analysis, more than in any previous year. Tan, who originally conceived the archive, says most of those unions are at smaller outlets where there are fewer barriers to organization. But workers from larger firms are getting in on the action too.

“If the goal is to hold these big tech companies accountable,” says Tan, himself a former tech worker who helped organize within Microsoft, “it’s not just one of these groups of workers who’s going to be able to do it. It’s the combined strength of them.”

The fight against “digital slavery”

Nader Awaad knows where to find Uber drivers with time to spare. He approaches them while they are idle in the parking lots outside London’s bustling airports, waiting for customers. Awaad hands them a leaflet and talks to them about joining a union, patiently hearing them make the same complaints he’s heard echoed across the industry.

Gig drivers aren’t the white-collar software developers you might picture when you think of a tech worker, but they make up a huge and growing group of tech employees. Over the last year, they have become increasingly vocal about several basic demands: for better pay, increased safety, a way to seek recourse if they are unfairly kicked off a company’s app UK other South Africa, drivers have brought Uber to court. In the U.S., DoorDash drivers went on an unprecedented, countrywide strike over plunging pay. In Hong Kong other mainland China, food delivery workers organized strikes for better pay and safety. In Croatia, Uber drivers held a press conference and a strike, saying their payments were late. “We feel like digital slaves,” one union member said.

In October 2021, Awaad helped organize a demonstration among drivers to protest termination without chance for appeal.

WIKTOR SZYMANOWICZ/NURPHOTO VIA AP

Awaad started driving for Uber in 2019 after being laid off from his previous job as a senior manager. He immediately felt the industry’s problems. “It reminded me of reading Charles Dickens,” he says. “The level of exploitation. The level of deprivation. I said, ‘I can’t believe it.’” Just as quickly, he realized he was not alone. Another driver he met at Heathrow sympathized. He looked around for a union to join, and by April 2019 he was a member of United Private Hire Drivers, a branch of the Independent Workers Union of Great Britain. He is now the elected chair.

His local membership of 900 or so drivers echoes those global problems, and he’s helped organize pickets and strikes, but he says the companies are refusing to engage in open dialogue. Awaad says drivers have to stay on the road for 12 or 14 hours a day to earn enough to get by.

in a landmark case Last February, the UK’s Supreme Court ruled that drivers are entitled to holidays, pensions, and a minimum wage. Several unions say Uber has avoided those new obligations, but the European Commission has also taken notice of the problem. It issued a directive in December to “improve the working conditions in platform work,” meaning new rules will follow.

Nader Awaad joined United Private Hire Drivers, a branch of the Independent Workers Union of Great Britain, in 2019. He is now the elected chair.

Nader Awaad joined United Private Hire Drivers, a branch of the Independent Workers Union of Great Britain, in 2019. He is now the elected chair.

COURTESY PHOTO

Then there’s the problem of algorithmic discrimination. Companies use algorithms to verify that drivers are who they say they are, but face-recognition technology is notoriously worse at recognizing nonwhite faces than white ones. In London, the vast majority of drivers are people of color, and some are getting removed from the platforms because of that gap.

Termination without a chance for appeal was a major motive for a strike Awaad helped organize in October. About 100 drivers rallied in the brisk London air, holding a large black banner with “End unfair terminations, stop ruining lives” written in white. In the background, protesters held signs with photos of drivers. “Reinstate Debora,” one of them said. “Reinstate Amadou,” said another.

During that rally, United Private Hire Drivers announced a discrimination complaint it had filed on the basis of the face-recognition errors. “We expect the court to come heavy on Uber because it happens in other countries, not only in our country,” Awaad says.

“At first I don’t think I understood how big the moment was going to be,” Field says. By the afternoon, big-name celebrities were voicing their support.

The drivers who do get work face other dangers. Covid exposure is an ongoing concern. So is assault—Awaad has spoken with drivers who have been attacked and robbed of their cars. He plans to organize a protest in front of the UK parliament to demand safety measures, and has been reaching out to other unions representing drivers, hoping to form a coalition and get the companies to act.

“We have two drivers who were killed in Nigeria. we have a driver who was killed on the 17th of February in London. We have, on a daily basis, attacks against the drivers,” Awaad says. “It’s not something that has to do with London only. It’s a global issue.”

Busting union busters

In September, workers at Imperfect Foods who had voted to unionize found that their employer was prepared to play the role of union buster. The same thing happened in November at HelloFresh, another grocery delivery service, whose workers in Aurora, Colorado, reported bullying and intimidation from management. When workers at an Amazon warehouse in Alabama held a vote in April on whether to unionize, the company interfered so extensively that the US National Labor Relations Board ordered a do over. (In a separate settlement, the agency said Amazon must allow its workers to freely organize unions.)

Such tactics are spreading, according to Yonatan Miller, a volunteer with the Berlin chapter of the Tech Workers Coalition. “Germany has a strong tradition of social compromise and social partnership, where companies are not as adversarial or hostile,” Miller says. “This is something that you’re kind of seeing imported from the US—this kind of US-style union-busting industry.”

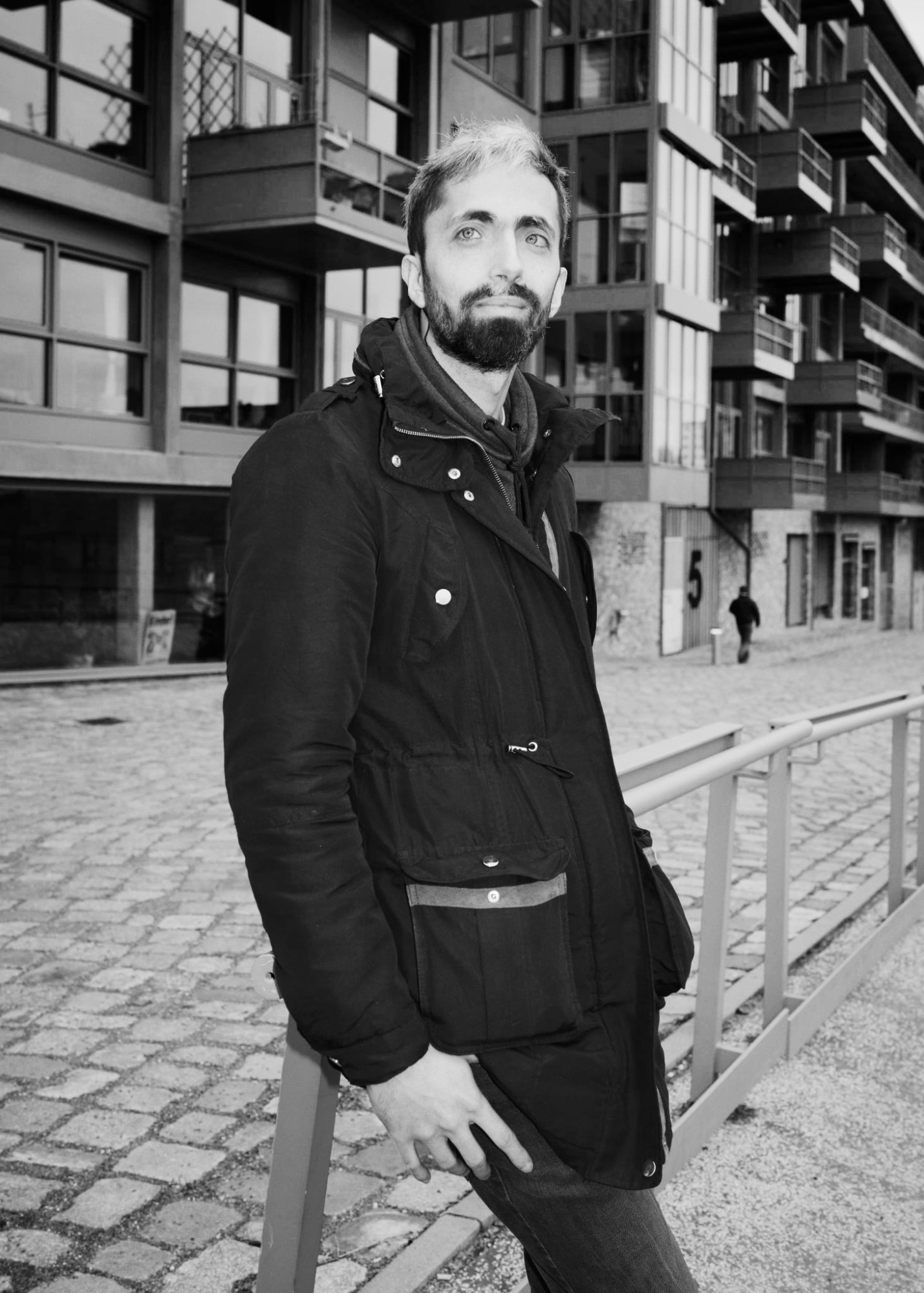

Yonatan Miller is a member of the Tech Workers Coalition, a grassroots, volunteer-led organization with 21 chapters globally.

Yonatan Miller is a member of the Tech Workers Coalition, a grassroots, volunteer-led organization with 21 chapters globally.

ULI KAUFMANN

The Tech Workers Coalition is a grassroots, volunteer-led organization with 21 chapters globally. Miller got involved in 2019 and still remembers the first meeting, in Berlin’s Kreuzberg neighborhood, with about 40 tech workers in attendance. “Most of us were, as they say, in Germany, newcomers. And some of us were from Arabic or Muslim background,” he says. But most were from Latin America, Eastern Europe, or elsewhere in Europe.

The idea behind the coalition is to help find a global answer to a global problem, and in the Berlin chapter’s two years of operation, it has achieved plenty of tangible results. it helped organizers at the grocery app Gorillas, Germany’s first unicorn company, which fought bitterly against a workers’ council, a union-like organization within a company that negotiates rights for workers. So it helped raise funds for an Amazon warehouse worker in Poland who was fired in what the coalition says was retaliation for their union activity. When the HelloFresh workers were trying to unionize, the coalition chapter in Berlin organized a protest in front of the company’s headquarters in solidarity. Any time there’s need or want, the coalition comes in to provide training, advice, or support, much of it “happening more discreetly behind the scenes,” Miller says.

In his eyes, these efforts are bringing the tech industry closer to other industries’ standards. His labor organizing is inspired as much by the activity of teachers and health workers as it is by the Google walkout. The inability to mingle with these other workers is one reason the pandemic has been so frustrating—it cut off access to the bars and gatherings where complaints turn into ideas and, eventually, actions at a moment when the industry had just begun to accept the need for labor organizing. “We won the moral argument,” Miller says, “but we haven’t been able to flex it.”

Tech, with integrity

The dust from Frances Haugen’s testimony last October hadn’t yet settled when two former Facebook workers made an announcement. Sahar Massachi and Jeff Allen were launching the integrity institute, a nonprofit intended to publish independent research and help set standards for integrity professionals who work to prevent social platforms from causing harm. Both Massachi and Allen had been ruminating on the idea for a while. They’d worked to clean up platforms as part of Facebook’s integrity team; some of Allen’s research was leaked among the documents Haugen. Now they wanted to answer big questions: What does integrity work look like as a discipline? What does it mean to responsibly build an internet platform?