Researchers at MIT have created a new text selection interface for motor impaired individuals. People with severe physical disabilities can type to communicate with others, and often activate a switch or blink an eye to indicate a letter selection in a grid of letters on a computer screen. This approach to typing is painstaking and time consuming, and requires the individual to wait until their letter is highlighted by a computer, which cycles through them all in turn, before they can make their selection. In an effort to speed things up, these MIT researchers developed a new text selection interface, called Nomon, which attempts to predict the most likely letters a user will choose next, and gives them a more rapid selection process.

Typing offers people with severe motor impairments, such as locked-in syndrome, the opportunity to communicate. However, the mechanics behind the text selection process can be frustrating and time consuming. The typical setup involves the letters arranged in a grid formation, and the computer will cycle through them in sequence. When the desired letter is reached, the user can flick a switch or blink the eyes (depending on their motor abilities). Then the process begins all over again for the next letter.

This new system aims to streamline the process and uses probabilistic reasoning to predict the letters a user is likely to need next, based on their previous selections. The algorithm can try to guess the next word, which can significantly reduce the amount of typing required. Moreover, the way that letters are selected is different too.

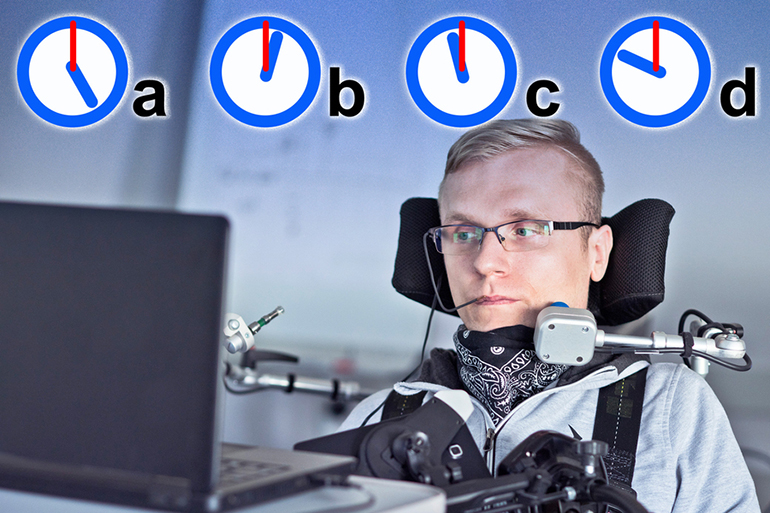

Each letter has a small clock face displayed beside it. The clock face is active, with a minute hand moving around it. A user can pick a particular letter by flicking the switch at the instant the minute hand passes noon on its clock face. That way there is no need for the computer to cycle through each letter. The user can merely locate the letter they want on the screen, wait a few seconds until the clock hand is in the right position and then flick the switch.

Nicely, the system also learns about the quirks of each user, so if you are typically a little late in flicking the switch, the system can learn this and adapt accordingly. So far, the Nomon system has led to improvements in typing speed compared with traditional systems currently used by motor impaired people.

“So far, the feedback from motor-impaired users has been invaluable to us; we’re very grateful to the motor-impaired user who commented on our initial interface and the separate motor-impaired user who participated in our study.” said Tamara Broderick, a researcher involved in the study. “We’re currently extending our study to work with a bigger and more diverse group of our target population. With their help, we’re already making further improvements to our interface and working to better understand the performance of Nomon.”

See a detailed video about the system:

Study in arXiv (not peer reviewed): A Performance Evaluation of Nomon: A Flexible Interface for Noisy Single-Switch Users

Via: WITH