But this spam content may not have had anything to do with the Chinese government after all, according to a report published on Monday by the Stanford Internet Observatory. “While the spam did drown out legitimate protest-related content, there is no evidence that it was designed to do so, nor that it was a deliberate effort by the Chinese government,” wrote David Thiel, the report’s author.

Instead, they were likely just the usual commercial spam bots that have plagued Twitter forever. These particular accounts exist to attract the attention of Chinese users who go on foreign networks to access porn.

So the “significant uptick” in spam was just a coincidence? The short answer is: very likely. There are two major reasons why Thiel does not think the bots are related to the Chinese government.

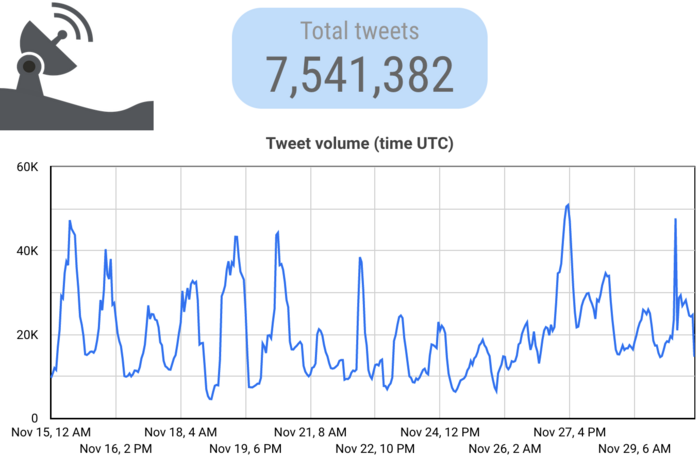

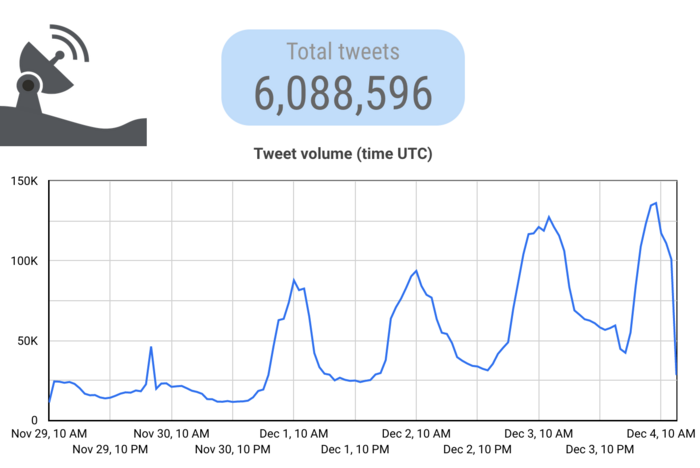

first of all, these accounts have been posting spam for a long time. And they sent out even more tweets, and more consistently, before the protests broke out, according to a data analysis on the activities of over 600,000 accounts from November 15 to 29. Another analysis shows they’ve also continued to push out spam even as discussions of the protests have died down.

Check out these two charts (for reference, the protests peaked around November 27):

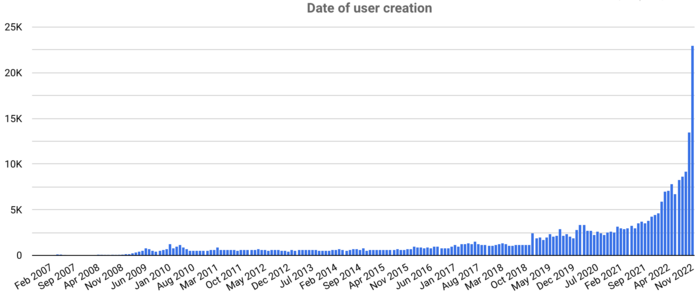

So did it just feel as if spam activity spiked during the protests? This graph shows that many more bot accounts were in fact created in November:

But Thiel emphasizes that content moderation takes time. People tend to ignore the effect called “survivorship bias”: older spam content and accounts are constantly being removed from the platform, but researchers don’t have data on suspended accounts. So a graph like this one only shows accounts that survived Twitter’s spam filters. That’s why November’s spike looks so big: they are new accounts created most recently to replace their dead peers and are still standing—but not all will survive, so they wouldn’t be there if we were to revisit this graph in, say, a few months. In other words, if you conducted a data analysis right after the protests, it would certainly seem that this kind of spam just started recently. But it’s not necessarily the full truth.

secondly, if the spam accounts were meant to bury information about the protests, they did a pretty poor job. While escort-ad spam featured many Chinese city names as keywords and hashtags, Thiel found that they did not target the hashtags actually used to discuss the protests, like #A4Revolution or #ChinaProtest2022, “which is what you would assume the government would be interested in jumping on if they were trying to silence things,” he tells me. Of the about 30,000 tweets he analyzed containing these more influential hashtags, “there’s no spam to speak of in there.”