Secreted beneath MIT’s Killian Court and accessible only through a subterranean labyrinth of tunnels, a clandestine lab conducts boundary-pushing research, fed by money siphoned from a Department of Defense grant. In these shadowed, high-tech halls, astrophysicist and astronaut Valentina Resnick-Baker, who is experiencing strange phenomena after an encounter with a planet-threatening asteroid, discovers she has the power of plasma fusion.

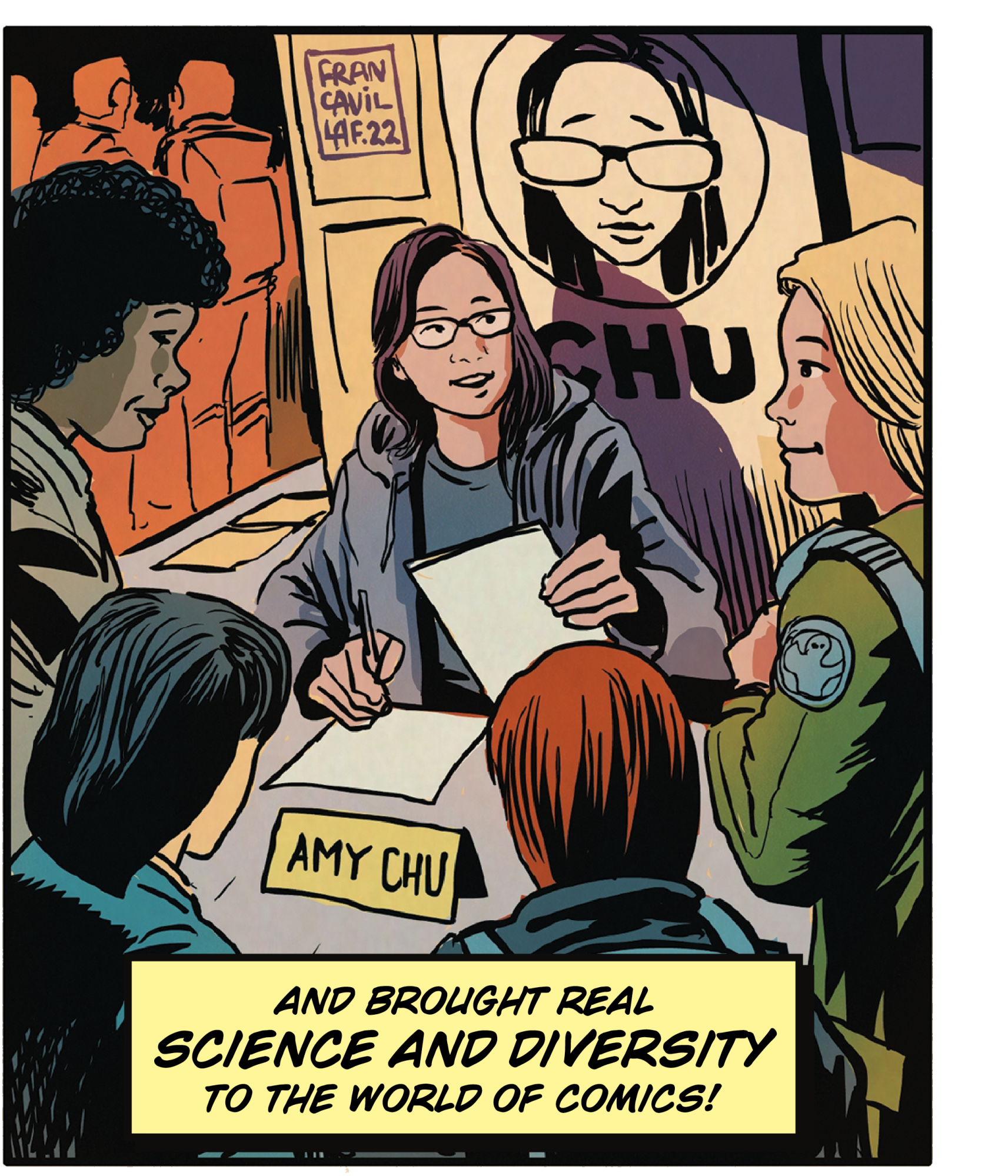

Resnick-Baker is the buff and brainy heroine of Summit, a 15-issue comic series created and written by Amy Chu ’91. The situations may be fictional, but the science is—broadly—real. (Chu did background research on plasma physics for the series, and when writing about the Batman villain Poison Ivy, she learned the basics of CRISPR so Ivy could deploy it to develop her own plant “kids.”) “The thing that has bothered me for a long time is that a lot of superhero stories are based on complete nonsense,” says Chu, 54. “Every story I do I try to ground in science.”

That a graduate of MIT prefers scientific plausibility to Kryptonite and radioactive spider bites may be the least surprising thing about Chu. At age 42, after a successful career spent largely in conference rooms, this first while management consultant entered her own alternate universe as a comic book writer. First through her publishing startup, Alpha Girl Comics, and now through work for heavyweights like Marvel and DC, Chu is reimagining a traditionally white male medium for girls, Asian-Americans and Pacific Islanders, and others who rarely see themselves in its color-saturated panels.

“A lot of superhero stories are based on complete nonsense. Every story I do I try to ground in science.”

Amy Chu

With comics, Chu is pursuing both a market opportunity and a social agenda, the latter familiar to the battle-scarred women of gaming. “All these people are screaming and hollering about comics: that they are dying because girls and women are killing them,” says Chu, referring to well-publicized misogyny directed at female creators and fans. “The future of comics hinges on the ability to get girls as readers.”

Making the team

Chu’s advocacy for women and girls began as advocacy for herself. Her parents, who immigrated from Hong Kong in 1968, moved the family around the country for her father’s positions in nuclear and, later, medical physics. In 1980 they ended up in Iowa City, where Chu balanced nerdy predilections (chess team, Dungeons & Dragons, text-based computer games) with a love of soccer. Her school had only a boys’ team, which she made—but the coach wouldn’t let her play. Chu’s family south of the school district and won.

In 1985 Chu moved to Massachusetts and embarked on a dual-degree program that required her to divide her time between MIT, where she studied architectural design, and Wellesley, where she pursued East Asian studies. But it was at MIT’s Phi Beta Epsilon fraternity that she met her destiny. Chu’s boyfriend at the time was a member there, and the girlfriend of one of his friends had been storing a large box stuffed with comics at the frat. Many were from First Comics, an alternative publisher specializing in spies, adventurers, and science fiction. “I read almost the entire box that summer,” says Chu, who previously had equated comics with superheroes. “It was a revelation.”

That’s the origin story. But Chu’s career in comics was a long way off. At Wellesley she did dabble in publishing, launching a cultural journal to prod the creation of a class in Asian-American studies. And after graduating from Wellesley in 1989, she moved to New York to cofound A. Magazine, a general-interest publication for Asian-American readers. But Chu knew that a startup magazine was unlikely to make enough money to survive, so after about a year she returned to Cambridge to finish her MIT degree. (A. lasted another eight years.)

After senior jobs at several Asian-American nonprofits in New York, Chu spent two and a half years in Hong Kong and Macau. While overseas she worked for billionaire businesswoman Pansy Ho, who owned a PR firm that produced events for luxury brands, and also worked with her family’s business developing tourism in Macau. Ho became a mentor.

Chu returned to the US to attend Harvard Business School and in 1999, MBA in hand, boarded the management-consulting train. Two years at the strategic consultancy Marakon helped her retire some Brobdingnagian student loans. Then Ho asked Chu to assist a few of her biotech investments in the US. That touched off close to a decade of business trips and PowerPoints, with Chu working as an independent consultant for Ho and others. “There was a great need at that time for biotech Red Sonjas,” she says, referring to the flame-haired mercenary about whom she also has written.

By 2010, Chu was burned out. Not only was her work intense, but she was raising two young children and exhausted from treatment for breast cancer. At the first Harvard Asian-American Alumni Summit, she connected with Georgia Lee, a friend who had engineered a 180-degree turn from consulting to writing and filmmaking. Lee laid out her new vision for a comics publisher targeting girls and women. Back then, female characters in established comics were reduced largely to cleavage and catsuits for the eyes of a presumed male readership.

The paucity of comics created by and for women awoke the sense of unfairness that had driven Chu back in Iowa. “I made the team in soccer,” she says. “I would make the team in comics.”

Becoming a writer

Chu and Lee’s startup, Alpha Girl Comics, debuted with a sci-fi Western by Lee called Meridien City. The founders planned to release work by other women later. As Chu prepared to take on the role of publisher, Lee urged her to learn every aspect of the business. So Chu signed up for a comic writing and editing program created by a former Marvel editor. “That’s where I got hooked,” she says.

Shortly after Alpha Girl released its first title, Lee couldn’t pass up the opportunity to direct a film in Hong Kong. By that time, Chu had written some stories of her own. “The whole thing shifted over to me,” she says. “So I said, I guess I will publish my stuff, with a bunch of artists.” (Like many comic writers, Chu crafts stories and collaborates with artists who draw the panels.)

Though her background doesn’t scream “comics creator,” it actually prepared her well for the work, she says. From the soulless labor of PowerPoint generation during her consulting career, she mastered economy of storytelling. And architectural design, her major at MIT, taught her to optimize space within constraints. (Chu compares fitting a full-blown fight scene into a 10-page comic to fitting a grand piano into a studio apartment: “You have to sacrifice things or it will be a bad experience.”)

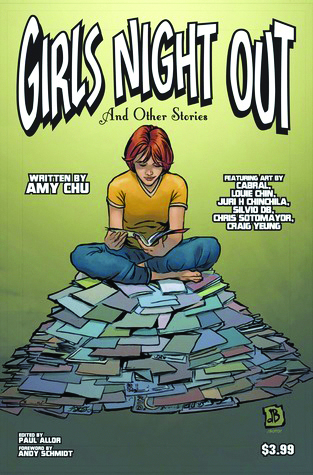

For Alpha Girl, Chu wrote and produced two titles. Girls Night Out is a three-volume series that follows the adventures of a woman with dementia and her friends who abscond from a nursing home. VIP Room is a one-off horror tale about five strangers imprisoned in a mysterious place. But hustling sales at conventions—Alpha Girl’s chief form of distribution—did not pave a path to prosperity. To raise her industry profile and make a little more money, Chu became a pen-for-hire, spinning new adventures for pop-culture icons developed by Marvel, DC Comics, and other publishers.

Chu’s decade-long career in comics has included a venture in independent publishing, graphic novels for young readers, and contemporary re-imaginings of the industry’s most iconic characters.

One notable creation was the story arc she developed in 2016 for Poison Ivy, a Batman villain who’d debuted in 1966 as a plant-obsessed eco-terrorist. Chu rethought the character as she produced Ivy’s first solo series, taking a sympathetic approach to her complicated morality. After getting feedback during a Wonder Con panel about the scarcity of Asian-Americans in comics, she added a South Asian male lead, partly inspired by a Jain classmate from MIT. (“Jains are extreme vegetarians, which of course was very interesting to Ivy,” she says.) Comics, says Chu, give her “a platform to increase representation and diversity.”

Comics also provide her with opportunities to get a little silly. In 2016, Chu began writing about the popular character Red Sonja, transplanting the sword-wielding barbarian from a fictional country and epoch to modern-day New York City. A few years later, Dynamite Entertainment and Archie Comics asked her to create a limited-series crossover between Sonja and Riverdale’s favorite female teen frenemies. “I thought that is so ridiculous I am just going to say no,” says Chu of what ultimately became Red Sonja & Vampirella Meet Betty & Veronica. “Then I thought, if I can do it and make it good, that is a testament to my ability.”

WITH inspiration

Chu soon became a sought after writer and is often asked to provide a fresh perspective on characters that may have been conceived decades ago. Ideas come from all over, including MIT Technology Review, which Chu calls “grounded in science and forward-thinking.”

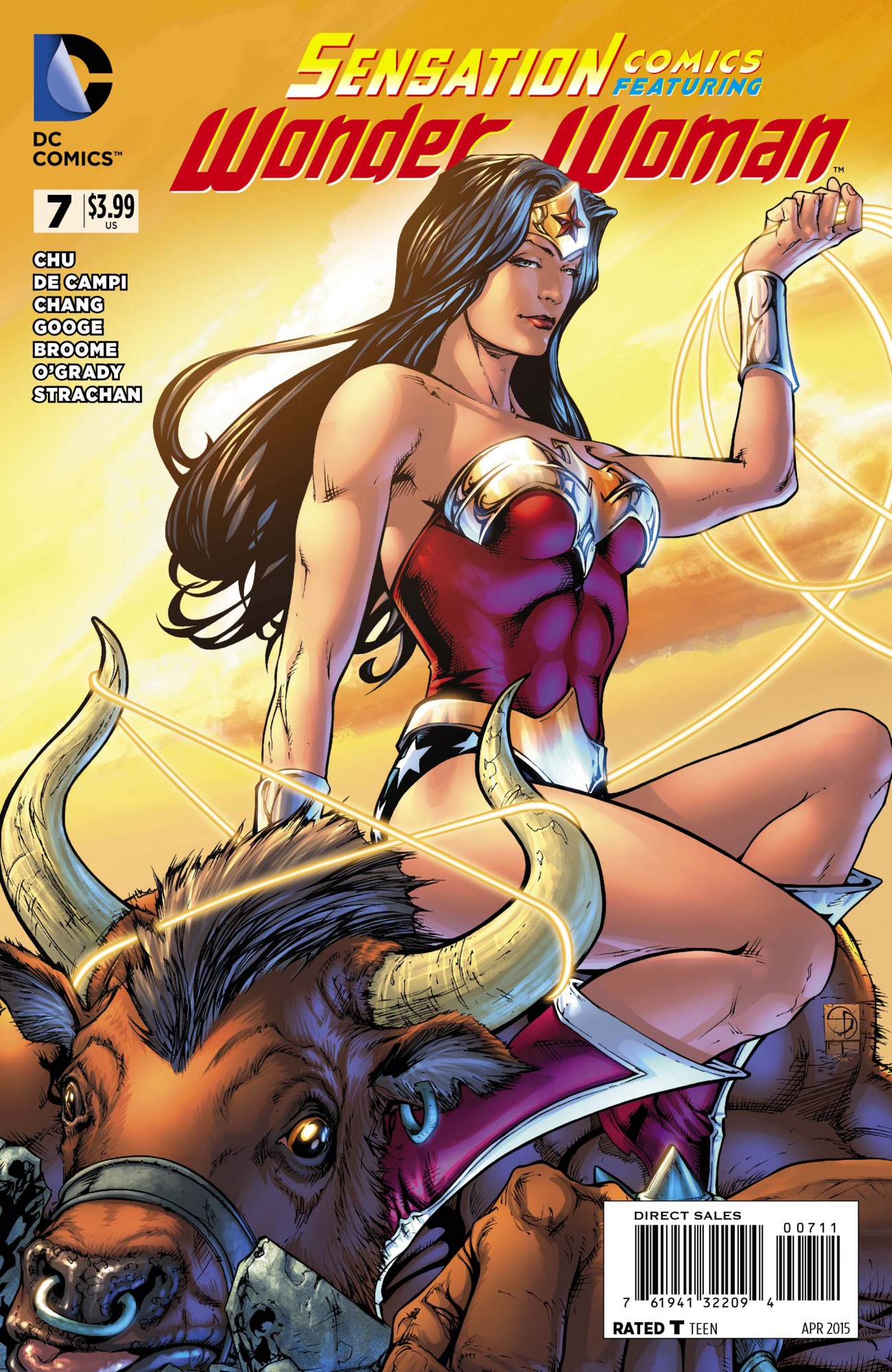

The Institute has proffered inspiration in other ways. At a Baltimore Comic Con where she was on a panel, Chu reconnected with Wisdom Coleman ’91. Coleman talked about his experiences as a combat pilot in Afghanistan and the women who served alongside him there. The lives of those women became the basis for Chu’s first Wonder Woman story, about a female pilot who wonders whether her own heroics are in fact the work of the Lady of the Golden Lariat. (They’re not.)

Characters like that female pilot and Resnick-Baker, the astrophysicist-astronaut at the heart of the Summit series, dress as Chu conceived them: like real women doing real work. Characters that Chu did not create, by contrast, often are rendered in the hypersexualized style she detests. There’s not much she can do about it. “A lot is dependent on the editor and the editor’s selection of the artist,” she says. One sign of progress, she observes, is the less exploitative approach of comic books targeting young audiences or produced by a growing cadre of female editors.

Chu sometimes will push back, as when an artist working on one of her books depicted Poison Ivy in a thong. “I literally was on a call where I walked them through the Victoria’s Secret catalog and told them what would be appropriate,” she says. “Somewhere between bikini and boy shorts is what I was imagining.” (The artist made the change.)

Today Chu gets so much work from mainstream publishers that she lacks time for Alpha Girl, which has not released a new title in several years. (Lee went on to write for television, notably for the Syfy and Amazon Prime Video series The Expanse.) She wants to revisit Alpha Girl, but “I keep getting stuff where I am like, I have got to write that because it is pretty cool,” she says. “Green Hornets? Yeah, I want to write Green Hornet! Wonder Woman? Of course!”

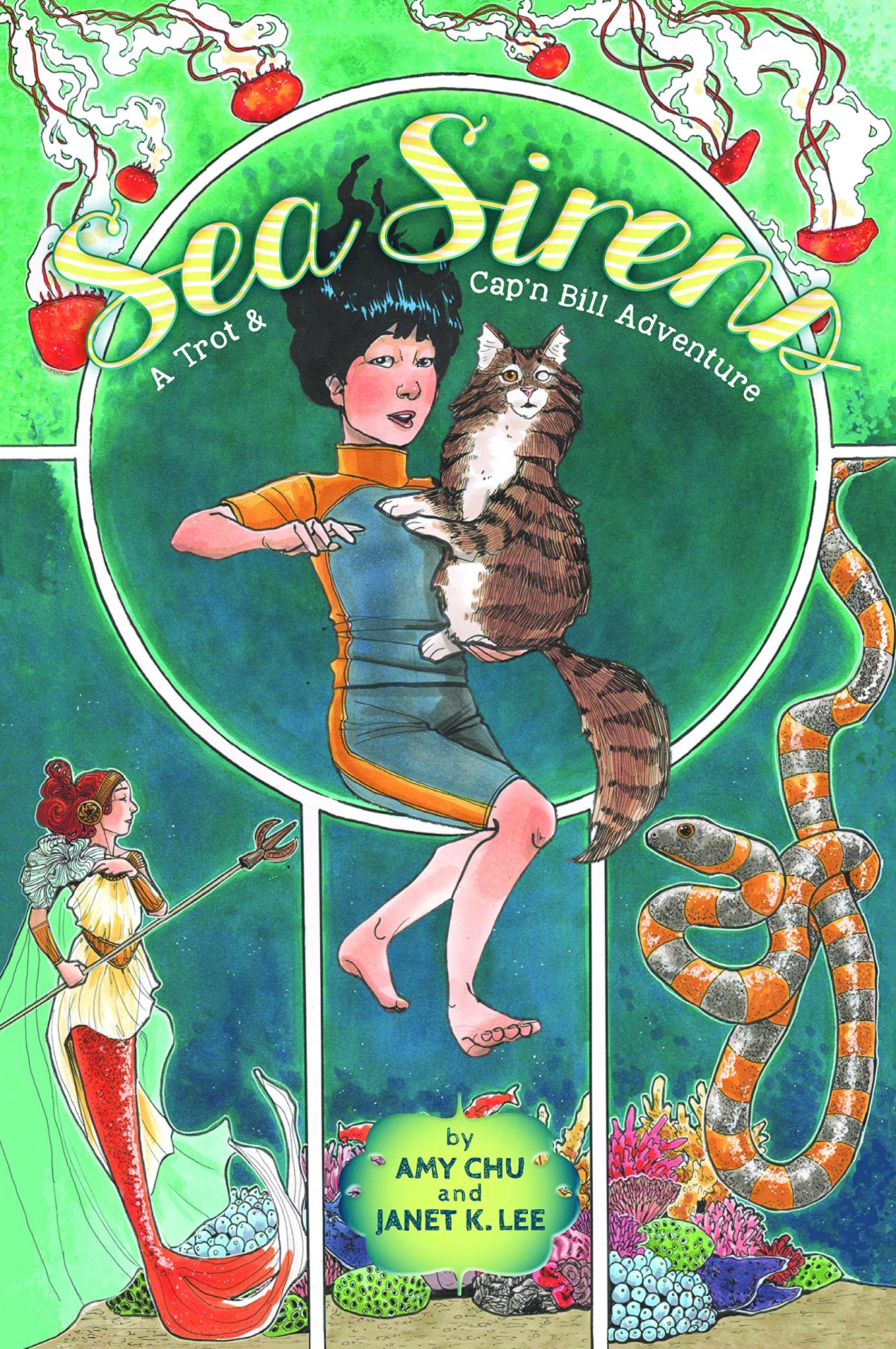

Chu also ventured into more traditional publishing. In 2019 and 2020 Viking released two volumes of Sea Sirens, a graphic novel for middle graders created by Chu and her friend Janet K. Lee, the Eisner Award–winning illustrator. Adapted from a 1911 underwater fantasy by Wizard of Oz author L. Frank Baum, Chu and Lee’s updated version reimagines the heroine, Trot, as a Vietnamese-American girl in Southern California. Her adult male companion is now a talking cat. “The idea of a young girl wandering around with a strange older man having adventures raises a lot of questions these days,” says Chu.

There are other demands on Chu’s time. Three years ago, she was recruited to write two episodes for the Netflix series DOTA: Dragon’s Blood, based on the popular video game. (A second, undisclosed Netflix program is in the works.) She’s also starting work on a comic series based on the Borderlands video games. On a different track, another MIT friend, Norman Chen ’88, who now runs the Asian American Foundation, recruited Chu to produce an overview of Asian-American history for grade-school students.

If Chu eventually does revive Alpha Girl, she may enjoy a new generation of readers and contributors. About 10 years ago the Girl Scouts created a Comic Artist badge, and Chu was flooded with requests to address the troops. “In a few years, a lot more women will have had this exposure,” she says. “If they are anything like me, they will get hooked.”